Glenn Mar (馬健安) was born in 1960 in Sydney. His grandfather, See Poy Mar (馬社培) arrived in Sydney in 1914 from Shachong (沙涌) village in Zhongshan. He came to work as a substitute manager at Wing Sang & Co, the famous banana wholesaler in Sydney in the period when preceding Wing Sang managers had returned to set up the Sincere Department Store and others in Hong Kong and China using ideas learned from Sydney department stores such as Anthony Hordern & Sons. See Poy Mar’s first wife died after he came to Australia and it was arranged that he would marry Daisy Yee whose brother was a Wing Sang colleague. Their eldest son Raymond (馬勵文), Glenn’s father, was born in Sydney in 1923.

Photo of Glenn’s grandmother Daisy Yee, his father and two uncles (from left: James, Daisy, Raymond and Arthur)

The family went back to live in Shachong in 1925 after See Poy was refused an extension to be able to continue living in Australia under the White Australia policy. See Poy died in about 1930 during a business trip, and his body was returned to his ancestral village for burial by the Wing Sang & Co. After See Poy passed away, his wife, Daisy, and her young children stayed in the village for a while. Then, in 1931, with the share assets she inherited from See Poy, she decided to move to Hong Kong probably due to the difficulty of life for a widow with no blood kin in the village. In doing so, she probably realised she risked losing control of the two village houses the family owned. Raymond received most of his education in Hong Kong but in 1938 was sent back to Sydney to earn a living to support the family. In 1940 Daisy and her sons Arthur and James (Jimmy) joined him in Sydney while her step-daughter decided to stay in Hong Kong.

Back in Sydney, Raymond at first worked as a bookkeeper for Wing Sang & Co. in Haymarket and involved in bookkeeping for the company for a few years. He then gained qualifications in accounting at a technical college in Sydney and went on to work as a public accountant with his own office in Ryde, Sydney. He met Bonnie nee Ping an accountant in Melbourne, married in Melbourne, then bought a home in Ryde where they raised six children. Bonnie’s mother had worked as a housekeeper in Melbourne and Bonnie had spent her school years living with her auntie’s family in Bairnsdale, Victoria. When he was young, Glenn’s parents would often take the family to Melbourne for Christmas to visit his mother’s family there.

Bonnie’s father was Wong Shee Ping (黃樹平), who was in Australia from 1908 to 1923. He worked in Chinese language newspapers, was a preacher and writer, and was a significant figure in establishing the Chinese republican movement (Kuomintang) in Australia. His father in turn was Wong Pang Tak (黃鵬德, aka Wong Pang) who probably came to Australia for goldmining c. 1869 or earlier from Kaiping, Guangdong. By the 1880s Wong Pang was a significant merchant in Melbourne’s Chinatown, and instrumental in establishing the Woah Hawp Canton Quartz Mining operation in Ballarat in 1882.

Bonnie’s maternal grandfather was Kim Sam a Chinese miner who later turned bootmaker. He married an Anglo-Irish woman who was a midwife. Bonnie was brought up in Melbourne and the country town of Bairnsdale. Bonnie and her extended family never learned to speak Chinese. Bonnie Mar lived in Ryde until she passed away in 2009 in her 80s. She is buried in North Ryde. She never visited China.

Glenn's mother Bonnie nee Ping aged 3 years old

Australia-China Connections

Glenn and his five siblings were brought up in an ‘Australian way’, somewhat ‘disconnected’ from the Sydney Chinese community. They mainly ate English-Australian meals at home and English was always the language at home. Glenn recalls that his father dropped his connections with Chinese culture when he moved to Australia and he objected to his wife’s idea of sending their children to a Chinese language school, saying ‘They are in Australia now’. Glenn guesses that his father worried that his children would not fit in and that he wanted them to assimilate. Glenn’s father never returned to Zhongshan and never talked about his life in China or made contact with his friends from his years in Hong Kong. Raymond passed away in Sydney in 1997. He was cremated, not buried according to Chinese custom. Glenn says this reflected his intention that the family ‘assimilate’.

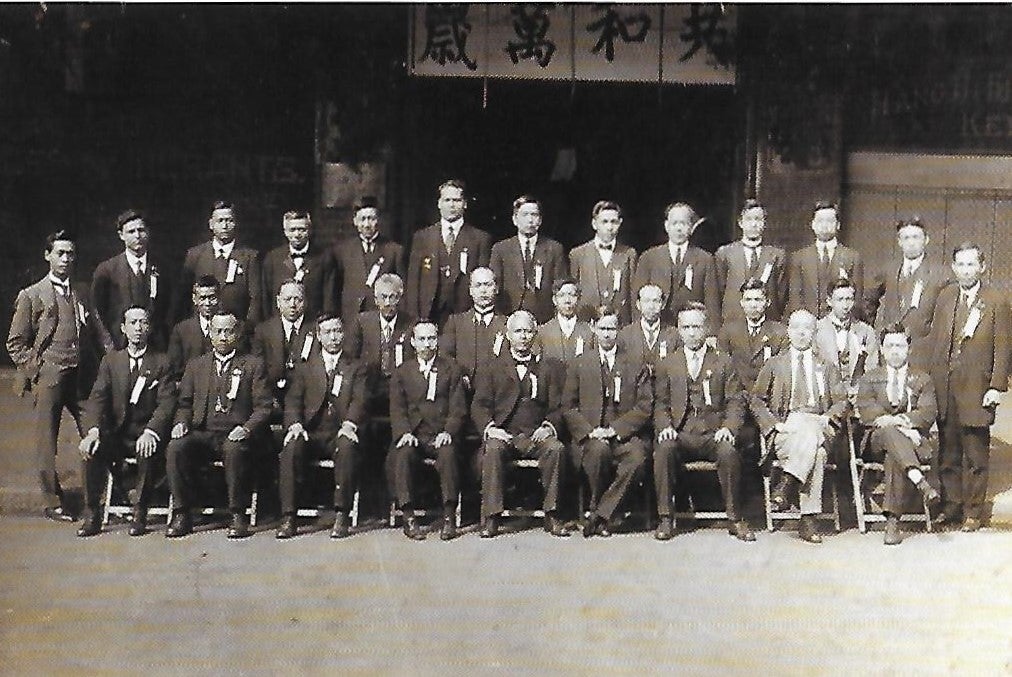

Recently, Glenn discovered that his grandfather, See Poy Mar, attended the First National Convention of the Kuomingtang in Sydney in 1920 and, more recently, that See Poy was one of the eight Chinese merchants who are recorded as the founding members of the Association of the Chinese Nationalist Party of Australasia (Kuomintang) in 1921. He also discovered that his father, Raymond, had been honorary treasurer of the Australian Chinese Association of New South Wales in the late 1940s. Glenn’s mother and his uncles inherited a small number of shares of the Sincere Company in Hong Kong. But the family no longer received dividends due to the company having re-structured.

First national convention of the Kuomingtang Sydney. Glenn's grandfather She Poy Mar was standing sixth from the left

Growing up in Australia, Glenn never experienced racial discrimination. He said, ‘if I had an accent due to my learning Chinese maybe it would have been different, or if I came to school with foreign food, for example, it could have been different’. Glenn married Jackie (蘭芳) who is originally from Hong Kong. His daughters can speak a little bit of Cantonese and have visited Hong Kong numerous times and China a few times.

Return Journey

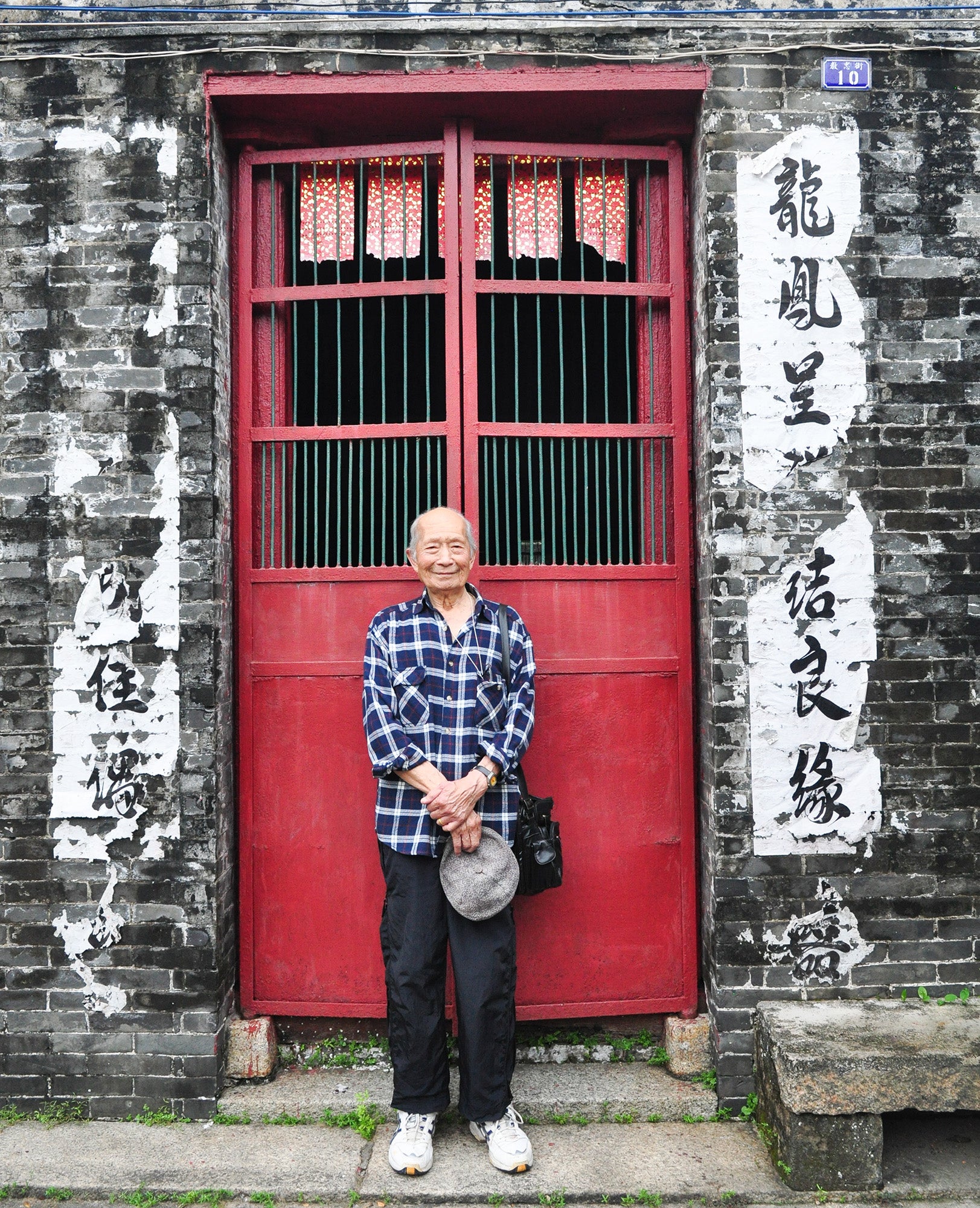

The first time Glenn went to Zhongshan was in 2015. The trip was facilitated by their family friend, Douglas Lam, who helped the Mar family locate their family home in Shachong. Altogether 18 members of the Mar family took part in this visit, including Glenn’s four siblings and his uncle James and his children.

During the trip, they visited their ancestral house in Shachong. The house was built by See Poy’s father (Glenn’s great-grandfather) around 1850. It was here that Daisy and her children lived after See Poy died and before they moved to Hong Kong. Glenn said, ‘it was moving for us and my daughter also…It’s terrific to know that part of your history [the house] is actually there. Yeah, we certainly feel lucky that it’s still there’.

The house is a modest one storey family home connected with the house next door in duplex fashion (divided from it by a common wall in the middle). The front wall of the house has a central door but no windows. The two rooms of the house, one behind the other, are separated by a wooden screen which can be passed through via a doorway. Above this door is a panel onto which is painted the scene of a river being crossed by a small steamship. The house has been vacant for a long time and the wooden beams are infested with termites. It is now being used as storage. Glenn’s uncle James recalled that the house had originally contained redwood and rosewood furniture, all of which is gone.

The Mar family were well received by the villagers and the village elder who is also a distant relative of the Ma family in Shachong. They had several big banquets and were presented with a genealogy book of the Mar family (the genealogy record is kept in Hong Kong) in which the names of Glenn’s grandfather, father and uncles were found. Unfortunately, they were unable to locate the remains of Glenn’s grandfather See Poy Mar by the time of the 2015 trip. Jars containing remains had been hidden in a secret place to protect from desecration during the Cultural Revolution and later restored to an appropriate place, however See Poy Mar’s jar had been misplaced in this operation. Following the visit, the village elder took action to locate the missing jar and restore it to the village burial site. The visit was especially meaningful and moving for Glenn’s uncle James (Jimmy) as it was the first time that he returned to his birthplace in 84 years and was again deeply moved when the family friend informed him that his father’s remains were located and that the friend had paid his respects on James’ behalf in 2016. James Mar passed away in 2017.

Glenn's uncle James Mar standing in front of his ancestral home in Shachong (2015)

While it may be possible to reclaim ownership of the Shachong house despite the lapse in time since Glenn’s grandmother left the house in 1931, this is not seen as an option that would be seriously considered by anyone in Glenn’s family. In Glenn’s view, ‘whatever’s past is past’.

In 2017, Glenn’s family (his wife Jackie and two daughters) returned to Zhongshan again as a side trip to a reunion visit of Jackie’s mother who was visiting relatives for the first time since fleeing to Hong Kong during the Cultural Revolution. Reflection of his return trips, Glenn said (in 2017), ‘it’s quite important to me to have that stronger link now and be able to think more, you know, you’re Chinese, what’s makes you Chinese, and what’s behind.’

The screen inside Glenn Mar’s ancestral house in Shachong (2017)

There is a genealogy book (jukpu) of the Mar Clan of Shachong village (1997 edition).

- Part one of the book is the family tree of the Shachong Mar Clan dated back to 1203 when the 1st generation moved to Zhongshan.

- Part two of the book listed the birth and death dates of each member (by family) from the 17th generation to the 22nd generation in the traditional Chinese calendar (stating the year of an emperor).

Mr Glenn Mar would like to share the jukpu on this website (please click the hyperlinks to view the documents) so that it can be read by many descendants of the clan.