Professor Kam Louie (雷金庆) was born in 1949 in Dutou village (渡头村) of Zhongshan. He is from a typical overseas Chinese family of those years. On his father’s side, Kam’s paternal grandfather (born 1885) went to Australia when he was young around the turn of the 20th century. He worked as a market gardener in Sydney and used the money he earned in Australia to buy land and build houses in his home village. Kam’s father (born 1918) also came to Australia to work as a cook after 1949 shortly after Kam was born. On his mother’s side, Kam’s maternal grandmother was from the famous Kwok (郭) family of the neighbouring Zhuxiuyuan village (竹秀园). Kam’s maternal grand-uncle was one of the founders of the Wing On Company (永安), a major department stores operator in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Kam’s maternal grandparents lived in Sydney. Kam was the oldest male member of the Louie family who stayed in the village with his siblings and other female members (his mother, grandmother and aunts) of the family.

Kam lived in a house similar to this style in ‘Si Fang Jing’ when he moved to Shekki with his mother and siblings in the mid-1950s. They lived on one floor of the house.

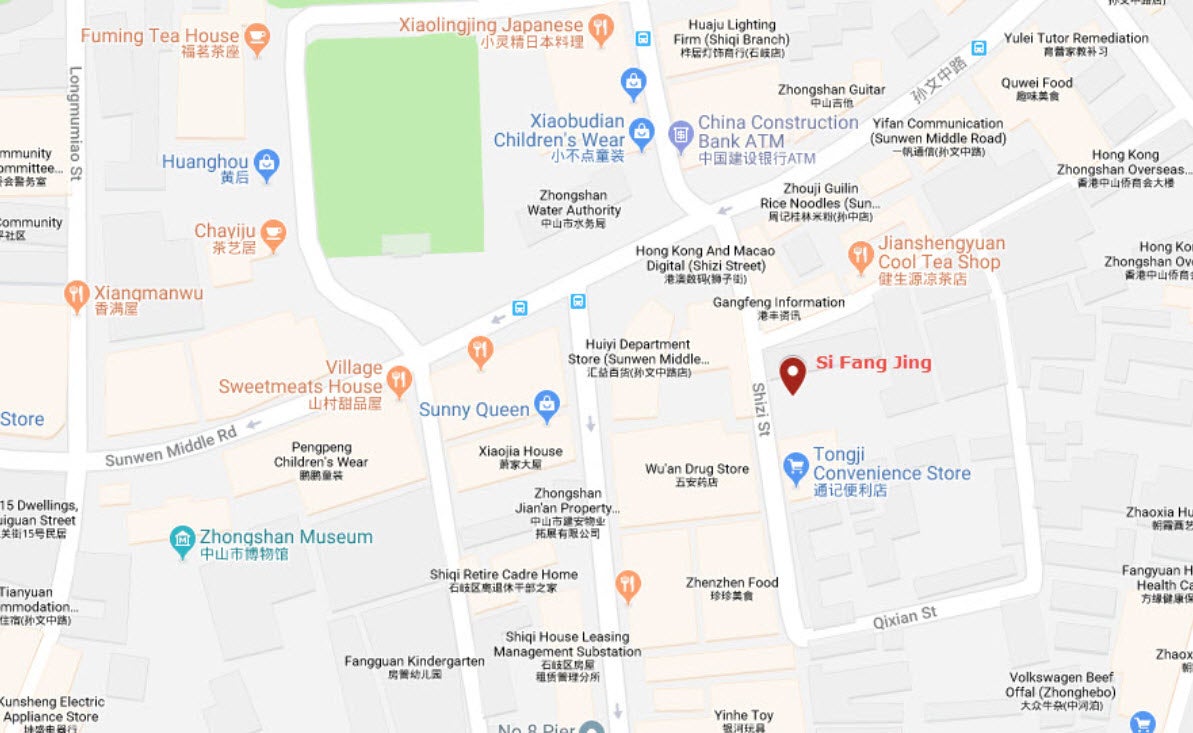

The location of Si Fang Jing on a Google map

When Kam was about five years old, he moved to Shekki (石岐)with his mother and siblings to live in a place called ‘Si Fang Jing’ (四方井) (in the east of Shizi Street), in a house owned by Wing On that served as accommodation for the company’s employees. Kam was able to live there because of his maternal grandmother’s connections to Wing On. In 1957 when Kam was about eight years old, he moved to Hong Kong and lived in Lock Road of Tsim Sha Tsui (尖沙咀). Two years later, in 1959, Kam at the age of 10 migrated to Australia with his eldest sister Bigg (碧媛), travelling on a passenger ship called the Taiyuan, to join his father in Sydney. A year later, Kam’s mother and younger brother Keith (霭麒) joined them in Australia.

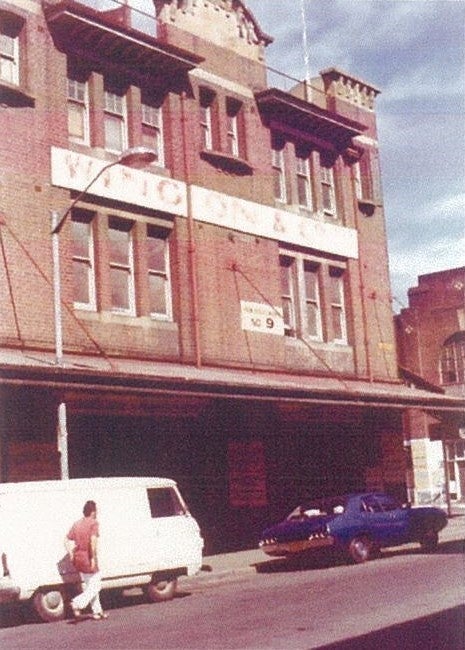

Wing On Department Store at Des Voeux Road, Sheung Wan in Hong Kong in the 1950s (courtesy of Howard Wilson)

When Kam first arrived in Sydney, he lived on the top floor of a three-storey Wing On warehouse on 37 Ultimo Road, Haymarket. Wing On Fruit Store (founded in 1897) was a leading banana wholesaler in Sydney during the 20th century. Other rooms on the upper floors of the building were occupied by Wing On’s employees and other young males who mostly came from Zhongshan. The ground floor of the building was Wing On’s office and warehouse. Kam enrolled at the nearby Ultimo Public School to study Year 3. The school had several Chinese students due to its proximity to Chinatown. Kam learnt English very quickly in the school, but he spoke Zhongshan to his family and all the Zhongshan residents who lived in the same Wing On building. This helped Kam maintain the fluency of his mother tongue and English. As he said, ‘I kept my Chinese because while I spoke English at school, at home everyone spoke Chinese, the whole environment was Chinese’. In the early-1960s, after living in the Wing On warehouse for about five years, Kam’s family moved to suburban Arncliffe. At that time Kam was in Year 8 at Cleveland Street Boys High School, so he commuted to Central Station by train each day.

The building of Wing On Fruit Store on Ultimo Road, Haymarket in the 1970s. Kam Louie lived on the top floor of this building with his family when he arrived in Sydney in 1959 until the early-1960s. (courtesy of Paul Kwok)

Ultimo Public School (established in 1880) on 177 Wattle Street, Ultimo. The school is close to Chinatown and was popular among Chinese families who lived in the neighbourhood. Alumni of the school include King Fong and William George Lee (FL2292544, State Archives & Records Authority of New South Wales, circa 1960)

Kam graduated from the University of Sydney with a major in Philosophy in 1972. In 1975, he received a Hong Kong government Commonwealth scholarship to study for a Master of Philosophy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In 1978 and 1979 Kam spent two years teaching at Nanjing University, before returning to Sydney to study for his doctorate under the supervision of Dr Mabel Lee at the University of Sydney (Dr Mabel Lee is the younger sister of Stanley Hunt and also Kam’s aunt-by-marriage). He carried out research in 1980-81 at Peking University to write his dissertation. After obtaining his doctorate in 1984, he taught at universities in New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong. Kam is an internationally well-known scholar in Chinese studies. He has published 18 books and numerous articles and reports in the areas of Chinese cultural studies and language pedagogy, modern and contemporary Chinese literature and classical Chinese philosophy. Kam was the Dean of the Arts Faculty at the University of Hong Kong from 2005 until his retirement in 2014. Since then he has been an Adjunct Professor at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and an Honorary Professor at Hong Kong University. Kam is married to Louise Edwards, a New Zealander and a scholar of Chinese history. They have a son and a daughter and live in Australia.

China-Australia Connections

Kam has maintained a close connection with China in his whole life. He was born and spent his early childhood in China, but significantly after arriving in Australia his connection to China continued through his five years living in the Wing On warehouse in the heart of Sydney’s Chinatown. Living in Chinatown enabled him to regularly interact with Chinese people. He recalls: ‘When I went to Dixon Street, I knew almost everybody and called them “Uncle” or “Auntie”, and we all spoke Zhongshan [dialect].’

At the University of Sydney, apart from studying Philosophy, Kam also devoted his time to learning and improving his Mandarin. He also attributed his interest in studying about China to his own experience as a Chinese migrant in Australia. At an interview in 2015, he said ‘as a Chinese person living in Australia, questions about my own identity were inevitably raised, so I became really interested in exploring this topic’ (Interview by Ruolan Yi, 26 March 2015).

One of Kam Louie’s English classes at Nanjing University in 1978. The class was for new teachers who had been “worker-peasant-solider” (Photo from the 2005 documentary of ‘The Story of Overseas Zhongshanese’ with the permission to use by Kam Louie.

Following his undergraduate studies in Australia, Kam returned to China, where he spent two years (1975-77) in Hong Kong to pursue his Masters’ degree and another two years (1978-79) to teach at Nanjing University in China. In 2005, Kam took up the position as the Dean of the Arts Faculty at the University of Hong Kong, after teaching in New Zealand and Australia for over two decades. He held that position for nearly ten years until his retirement in 2014. Kam has published widely on ‘Chineseness’. He said in an interview, ‘throughout my life, I have been trying to explain “China” to Westerners and explain the “West” to Chinese people’ (Interview by Ruolan Yi, 26 March 2015).

Kam is a life member of the Chung Shan Society of Australia, although he is not an active participant in the society. He attended the Worldwide Zhongshan Association Convention in Sydney in 2015, where he received the ‘Outstanding Chinese Scholar’ award (杰出华人优秀学者奖). Kam returned to Sydney after his retirement. In contrast to when he was young, when he knew almost everyone in Chinatown, today he no longer maintains a close relationship with the Chinese community in Sydney, especially after the passing of his grandparents and parents.

While Kam is less connected to the Chinese community in Sydney now, it seems he has passed on his connection to China to his children. Although Kam’s children are half-Chinese, both have learnt Chinese. His son has studied at Peking University and Tsinghua University in China, and his daughter majored in Chinese at university. As Kam explained, his children’s connections to China are not with Dutou village or Zhongshan, but with China and the Chinese culture as a whole. He compared the changing nature of this connection to the experiences of an Irish migrant descendant living in a foreign country. In his words: ‘You sort of say I know this is Irish beer or this is Irish dancing or whatever, you can talk about Irish [culture], but the village where they came from, they probably can’t say where’.

Return Journey

The first time Kam returned to Dutou village after he migrated to Australia was in 1972 to visit his dying grandmother. Although it was during the Cultural Revolution period, Kam was eager to return as he had not seen his grandmother or sister who stayed behind for nearly 15 years. Besides, he was interested in Marxism due to his study of the topic at the University of Sydney. In his words, ‘I really wanted to go back because in high school, and university, like many young people in those days, I was highly influenced by Mao, so I used to [go to] classes and study it… Also, I did the Marxism course which was introduced for the first time at Sydney University…so the Cultural Revolution was a real godsend for me because it allowed me to marry the two, politics and then being Chinese, so I really wanted to go back, and that’s why I went back’.

However, Kam’s first attempt to return to China was an ordeal to him. According to Kam, he was ‘stateless’ at that time as he was neither a naturalized Australian citizen nor a Chinese citizen. His only identity document was a certificate of identity issued by Hong Kong. Kam took a plane in Sydney and was supposed to change onto a connecting flight in Thailand. Unfortunately, the Thai authorities did not allow him to transit in Thailand due to his certification problem. He was sent back onto the plane and was unable to disembark until it reached its final destination in Paris. Kam recalled his experience, ‘that was really, really horrifying… I was really miserable. [I] went to the British Embassy, Chinese Embassy, Australian Embassy, and none of them would talk to me.’ Three days later, Kam was allowed to board on a plane to fly back to Sydney.

One week after he was sent back to Sydney, Kam tried to go to China again. The travel agent booked him a plane to Hong Kong via Singapore. This time, he successfully boarded on a connecting flight in Singapore for Hong Kong. After arriving in Hong Kong, he took a boat to Macau and then a bus to Zhongshan. This time, his journey was mostly smooth except ‘It took me a whole day just to get past customs…they searched everything’. Nevertheless, Kam was really pleased about his first return journey. As he described, ‘When I got back there, it was wonderful… this is really good because I was so enamoured by China, everything was wonderful’. He stayed in his ancestral house with his grandmother, sister and an aunt who came back from another village. ‘With my grandmother, whom I hadn’t seen for 15 years…I was completely spoiled by them’. Since that first trip, Kam returned to China again in 1973 and 1974. He travelled to his village frequently when he was studying in Hong Kong and teaching in China. He said, ‘I used to go back a lot, so I knew the people in the village really well.’

Now retired in Sydney, Kam still returns to Dutou village from time to time. The last trip he made to the village was in mid-2018. However, Kam says that his connection with his home village is diminishing, partly because the people he knew began to pass away. As he said, ‘in probably a few more years, [they] will be dead, and then when that generation goes, the connection will be less and less’. Kam also feels a sense of loss about the changes in his home village. In the last few decades, the wealthy residents of the village have moved out and built new big houses adjacent to the old village. The old houses in the original village are now rented to migrants who come from other provinces. Kam said: ‘Even the Zhongshan people, they are gone. You get in a taxi, and you go into the shops, they always speak Cantonese rather than Zhongshan [dialect]. In the village itself, Zhongshan is actually not spoken by that many people now. The younger generation prefers to speak Cantonese or Mandarin’.

Kam’s ancestral home in Dutou village. The remains of the painting on the façade of the house can still be seen (2018)

The next door neighbour was renovating their place. They used the front yard of Kam’s house to store their building materials (2018)

Kam still owns the ancestral home in Dutou village which was built by Kam’s grandfather (who passed away in 1957). It is a two-storey building in duplex style. There were elaborate paintings, colourfully decorated, some with gold gilding, on the exterior of the house, but all the that was scraped off on the eve of the Cultural Revolution. Now only remnants of the painting are visible on the facade. During the land reform period of the early 1950s, Kam’s family was classified as ‘landlord’ (later their status changed to overseas Chinese ‘Huaqiao’), and half of the house was confiscated and given to another family from the village who were poor peasants. Kam and his family lived in the bigger half of the house. In the early 1980s, all confiscated houses in the village were returned to the former ‘landlords’, and the deed to the house is now in Kam’s name. A very distant uncle lived in the house through the 1980s and 1990s, but he died about ten years ago. Since then the property has been vacant.