Choy ancestral hall, Waisha village, Zhuhai

The Choy lineage’s native place is Waisha village, situated today in the Zhuhai Special Economic Zone, an area that was originally part of Zhongshan County (Mandarin: Xiangshan 香山縣). Formerly the village was located close to the sea but in recent years a large area for housing was reclaimed from the sea, meaning the sea is now more than 3 kilometres east of the village.

The area of Waisha village. The newly reclaimed area is to the right (east side) of the village

The Choy lineage’s ancestral hall is located at the front (southeast side) of Waisha village, facing the village’s fields. The primary purpose of the hall was to house the tablets of the lineage’s male ancestors. These small wooden tablets, inscribed with names of the deceased members of the lineage embodied the ancestors’ presence and were worshiped with prayers and offerings of incense and food. The hall would also originally have housed the lineage’s written genealogy which was updated whenever a male member of the clan was born.

Waisha village showing the position of the Choy ancestral hall

The most notable link between Waisha and Australia was in the person of Hing Choy (蔡興) (1869-1957) who was born and grew up in the village after attending school in Hong Kong and Shanghai he migrated to Australia in 1889 where he found success in the fruit and vegetable trade. In 1900 he became one of the founders of the Sincere department store chain, along with his friend from his days in Sydney, Ying-piu MA. He left Sydney for Hong Kong in the first decade of the 20th century and along with his brother, Chong CHOY (蔡昌)(1877-1953), he founded the Sun Company which had stores in Hong Kong and Canton before opening the Sun Company department store in Shanghai in 1936. Hing Choy built a large mansion for his family in Hong Kong, at 2 Park Road, Mid-Levels.

The mansion in Hong Kong built by Hing Choy in the early 20th century (courtesy of Howard Wilson)

As in most parts of southern China, in Zhongshan ancestral halls, along with deity temples, were the most prominent buildings in a village. The ancestral halls announced a lineage’s presence and prestige to the world and acted as a focal point for lineage members in ritual, social and political events. Lineages remained important in the Pearl River Delta into the mid-1900s (Faure, 2007, 341-342), though with the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 and the widespread embrace of modernity, their centrality in people’s lives declined.

The ancestral hall in the Mao era (1949-1976)

The 1952 Land Reform enacted by the new People’s Republic saw all lineage lands confiscated and divided among the tenant farmers occupying them (Siu, 2016, 152). Collectivisation was followed in 1958 by the establishment of communes.

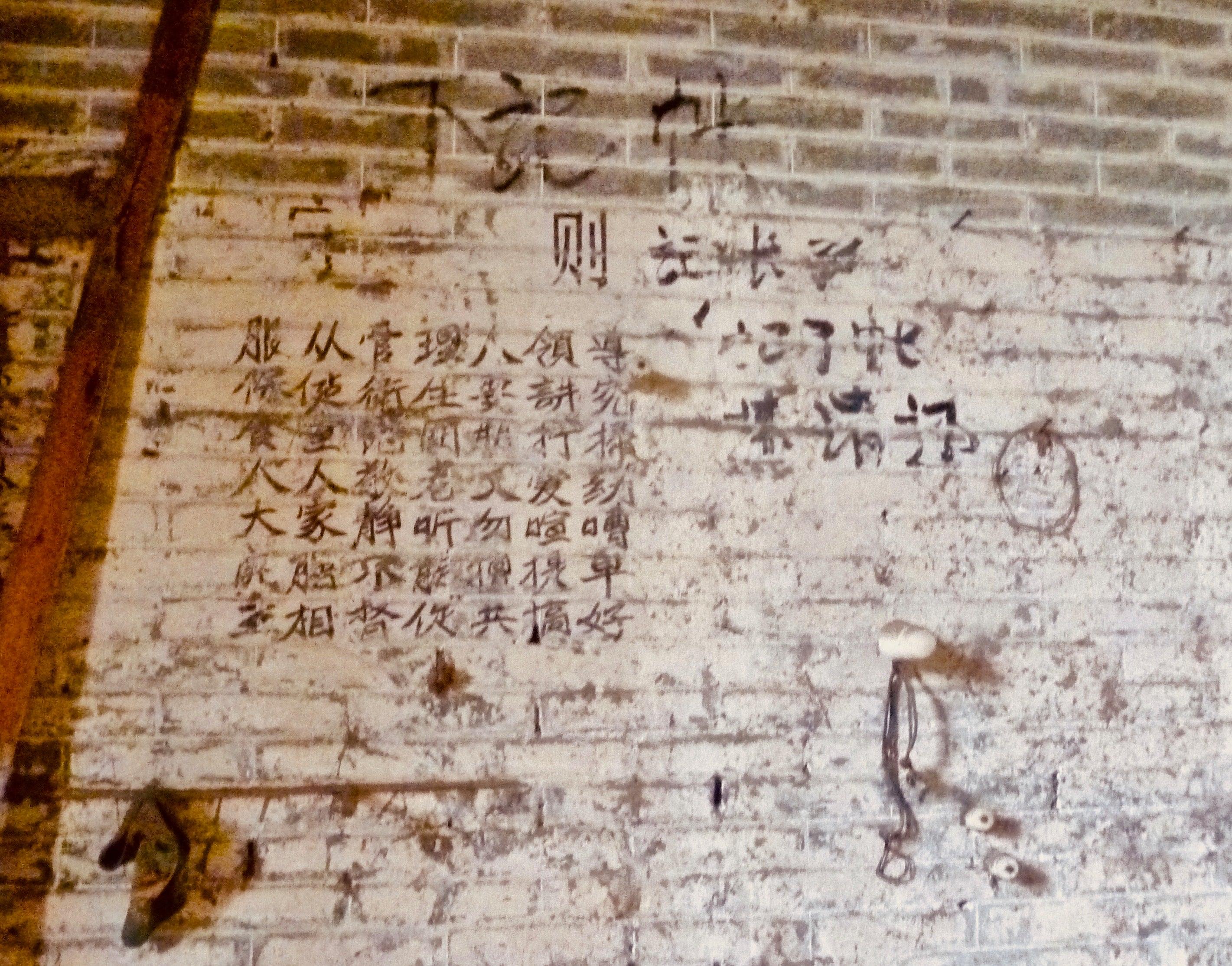

Inscriptions that were still visible on an interior wall of the Choy ancestral hall in 2014 suggest it had been turned into a communal dining room.

The writing on one of the internal wall’s suggests the hall was used as a communal dining hall during the Mao era (courtesy of Howard Wilson)

These lines of text read as follows (the question marks referring to characters which are too faded to identify clearly):

服从管理人领导 Obey the directions of the managers

保健卫生要讲究 Pay attention to health and hygiene

食室范围勤打扫 Clean the dining hall area frequently

人人敬老又爱幼 Everyone respects the elders and loves the children

大家静听勿喧嘈 Everyone listens quietly and does not make noise

? 膳不能擅提早 Cannot have the meal (?) early without permission

互相督促共搞好 Supervise each other to achieve these

The ancestral hall restored

After the Reform era began in the last 1970s the ancestral hall was left derelict. When Ronald Choy, grandson of Hing Choy, visited Waisha in 2014 he found that a tree was growing through the roof of the hall and that the building’s condition had seriously deteriorated. He and other members of the Choy lineage then began raising funds to restore the hall, a project which began in 2017.

The ancestral hall in 2014, prior to restoration (courtesy of Howard Wilson)

The ancestral hall during restoration in 2017. The high building in the background (above the red banner) is the school which was built by the Choy brothers in the early 20th century

A team of professional restorers were contracted to carry out the work, replacing only those elements of the structure which could not be salvaged. Much of the roof was replaced using traditional materials and the floors were replaced using new terracotta tiles. The building’s original brickwork has been retained (but repainted).

New terra cotta tile floor being laid inside the hall in 2017

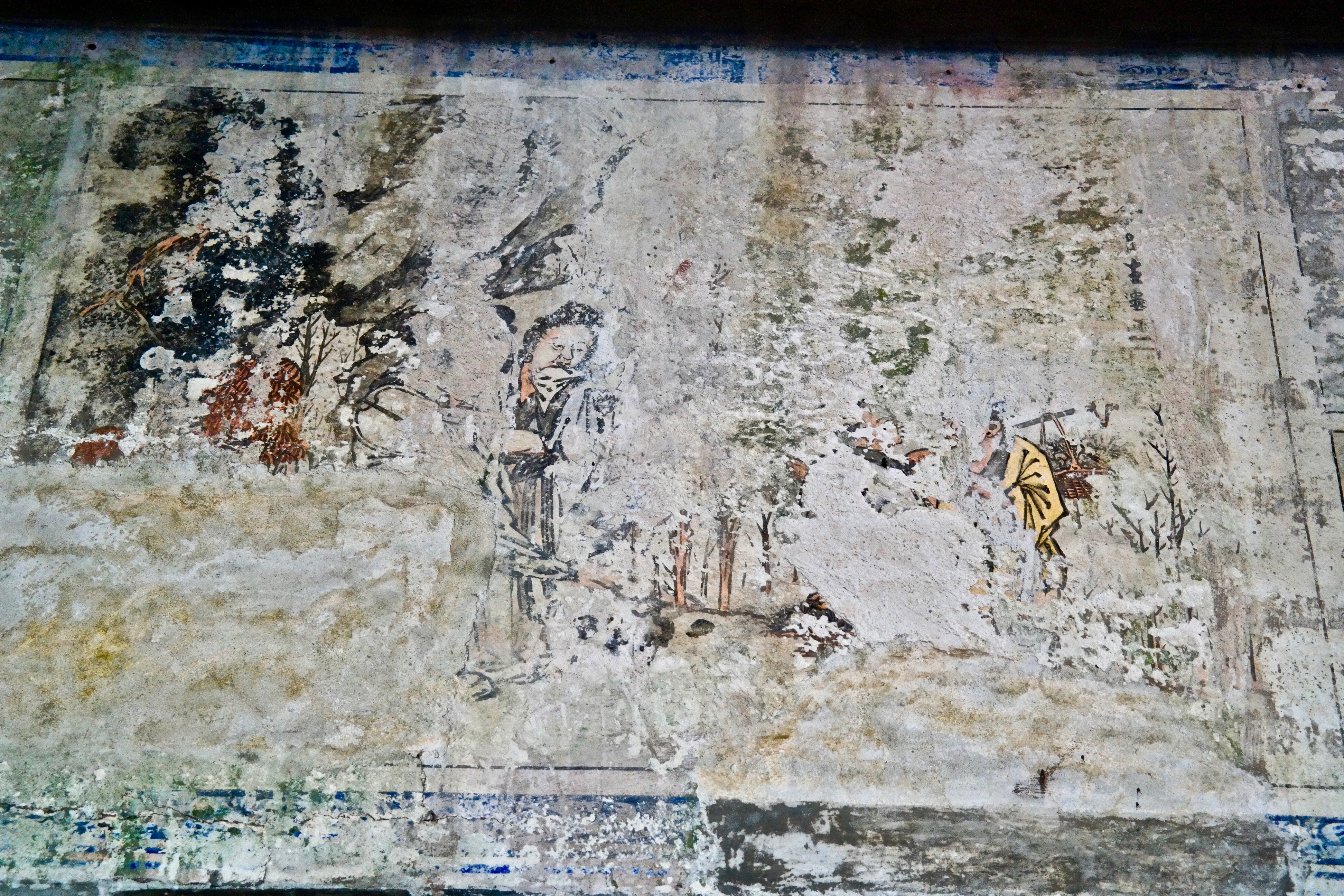

During the Cultural Revolution, some of the wall painting in the hall were covered over with stucco-cement. This has been chipped off to reveal the paintings beneath. In general, although the wall paintings are mostly in poor condition, they have not been repainted or touched up in the course of the restoration project (this accords with international heritage conservation guidelines).

A layer of stucco-cement being chipping off to reveal the wall painting underneath (2017)

One of the deteriorated interior wall paintings (2017)

References

Faure, D. (2007) Emperor and Ancestor: State and Lineage in South China, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Siu, H. F. (2016)Tracing China: A Forty-Year Ethnographic Journey, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.